Americans and ‘Cancel Culture’: Where Some See Calls for Accountability, Others See Censorship, Punishmenthttps://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/05/19/americans-and-cancel-culture-where-some-see-calls-for-accountability-others-see-censorship-punishment/

People have challenged each other’s views for much of human history. But the internet – particularly social media – has changed how, when and where these kinds of interactions occur. The number of people who can go online and call out others for their behavior or words is immense, and it’s never been easier to summon groups to join the public fray.

The phrase “cancel culture” is said to have originated from a relatively obscure slang term – “cancel,” referring to breaking up with someone – used in a 1980s song. This term was then referenced in film and television and later evolved and gained traction on social media. Over the past several years, cancel culture has become a deeply contested idea in the nation’s political discourse. There are plenty of debates over what it is and what it means, including whether it’s a way to hold people accountable, or a tactic to punish others unjustly, or a mix of both. And some argue that cancel culture doesn’t even exist.

To better understand how the U.S. public views the concept of cancel culture, Pew Research Center asked Americans in September 2020 to share – in their own words – what they think the term means and, more broadly, how they feel about the act of calling out others on social media. The survey finds a public deeply divided, including over the very meaning of the phrase.

Who’s heard of ‘cancel culture’?

As is often the case when a new term enters the collective lexicon, public awareness of the phrase “cancel culture” varies – sometimes widely – across demographic groups.

Overall, 44% of Americans say they have heard at least a fair amount about the phrase, including 22% who have heard a great deal, according to the Center’s survey of 10,093 U.S. adults, conducted Sept. 8-13, 2020. Still, an even larger share (56%) say they’ve heard nothing or not too much about it, including 38% who have heard nothing at all. (The survey was fielded before a string of recent conversations and controversies about cancel culture.)

Familiarity with the term varies with age. While 64% of adults under 30 say they have heard a great deal or fair amount about cancel culture, that share drops to 46% among those ages 30 to 49 and 34% among those 50 and older.

There are gender and educational differences as well. Men are more likely than women to be familiar with the term, as are those who have a bachelor’s or advanced degree when compared with those who have lower levels of formal education.1

While discussions around cancel culture can be highly partisan, Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents are no more likely than Republicans and GOP-leaning independents to say they have heard at least a fair amount about the phrase (46% vs. 44%). (All references to Democrats and Republicans in this analysis include independents who lean to each party.)

When accounting for ideology, liberal Democrats and conservative Republicans are more likely to have heard at least a fair amount about cancel culture than their more moderate counterparts within each party. Liberal Democrats stand out as most likely to be familiar with the term.

How do Americans define ‘cancel culture’?

As part of the survey, respondents who had heard about “cancel culture” were given the chance to explain in their own words what they think the term means.

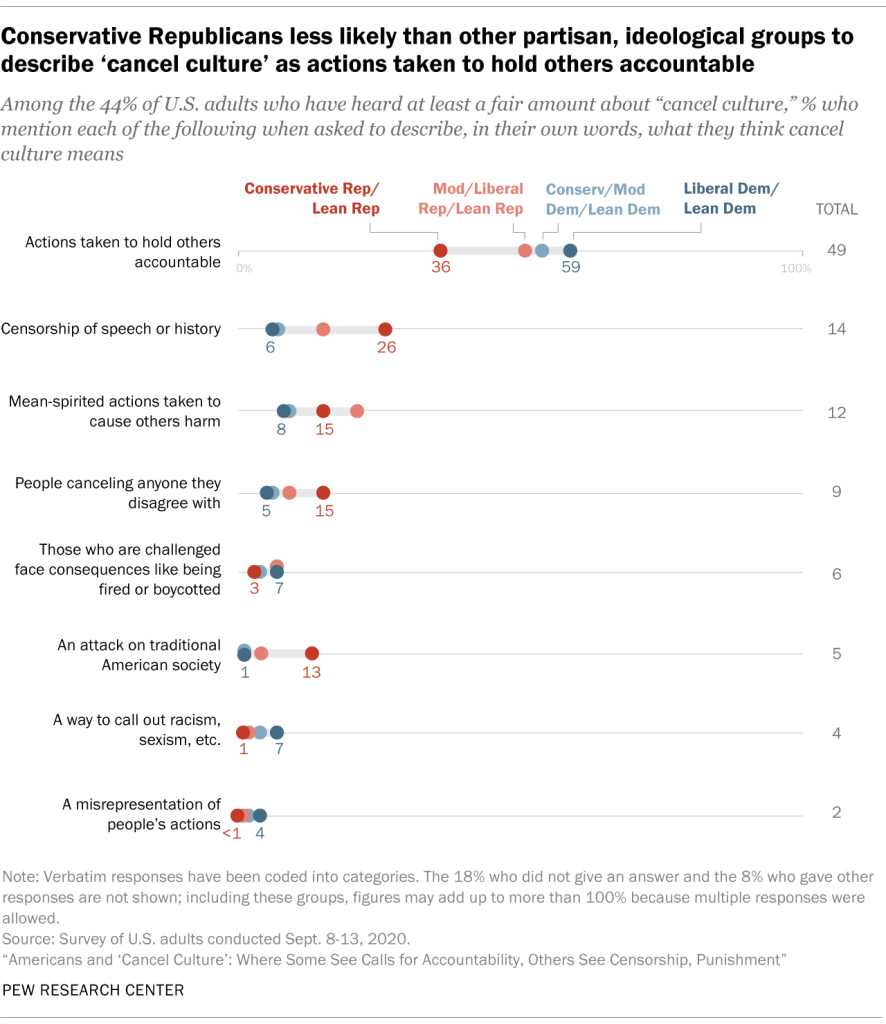

The most common responses by far centered around accountability. Some 49% of those familiar with the term said it describes actions people take to hold others accountable

A small share who mentioned accountability in their definitions also discussed how these actions can be misplaced, ineffective or overtly cruel.

Some 14% of adults who had heard at least a fair amount about cancel culture described it as a form of censorship, such as a restriction on free speech or as history being erased:

A similar share (12%) characterized cancel culture as mean-spirited attacks used to cause others harm:

Five other distinct descriptions of the term cancel culture also appeared in Americans’ responses: people canceling anyone they disagree with, consequences for those who have been challenged, an attack on traditional American values, a way to call out issues like racism or sexism, or a misrepresentation of people’s actions. About one-in-ten or fewer described the phrase in each of these ways.

There were some notable partisan and ideological differences in what the term cancel culture represents. Some 36% of conservative Republicans who had heard the term described it as actions taken to hold people accountable, compared with roughly half or more of moderate or liberal Republicans (51%), conservative or moderate Democrats (54%) and liberal Democrats (59%).

Conservative Republicans who had heard of the term were more likely than other partisan and ideological groups to see cancel culture as a form of censorship. Roughly a quarter of conservative Republicans familiar with the term (26%) described it as censorship, compared with 15% of moderate or liberal Republicans and roughly one-in-ten or fewer Democrats, regardless of ideology. Conservative Republicans aware of the phrase were also more likely than other partisan and ideological groups to define cancel culture as a way for people to cancel anyone they disagree with (15% say this) or as an attack on traditional American society (13% say this).

Does calling people out on social media represent accountability or unjust punishment?

Given that cancel culture can mean different things to different people, the survey also asked about the more general act of calling out others on social media for posting content that might be considered offensive – and whether this kind of behavior is more likely to hold people accountable or punish those who don’t deserve it.

Overall, 58% of U.S. adults say in general, calling out others on social media is more likely to hold people accountable, while 38% say it is more likely to punish people who don’t deserve it. But views differ sharply by party. Democrats are far more likely than Republicans to say that, in general, calling people out on social media for posting offensive content holds them accountable (75% vs. 39%). Conversely, 56% of Republicans – but just 22% of Democrats – believe this type of action generally punishes people who don’t deserve it.

Within each party, there are some modest differences by education level in these views. Specifically, Republicans who have a high school diploma or less education (43%) are slightly more likely than Republicans with some college (36%) or at least a bachelor’s degree (37%) to say calling people out for potentially offensive posts is holding people accountable for their actions. The reverse is true among Democrats: Those with a bachelor’s degree or more education are somewhat more likely than those with a high school diploma or less education to say calling out others is a form of accountability (78% vs. 70%).

Among Democrats, roughly three-quarters of those under 50 (73%) as well as those ages 50 and older (76%) say calling out others on social media is more likely to hold people accountable for their actions. At the same time, majorities of both younger and older Republicans say this action is more likely to punish people who didn’t deserve it (58% and 55%, respectively).

People on both sides of the issue had an opportunity to explain why they see calling out others on social media for potentially offensive content as more likely to be either a form of accountability or punishment. We then coded these answers and grouped them into broad areas to frame the key topics of debates.

Some 17% of Americans who say that calling out others on social media holds people accountable say it can be a teaching moment that helps people learn from their mistakes and do better in the future. Among those who say calling out others unjustly punishes them, a similar share (18%) say it’s because people are not taking the context of a person’s post or the intentions behind it into account before confronting that person.

In all, five types of arguments most commonly stand out in people’s answers. A quarter of all adults mention topics related to whether people who call out others are rushing to judge or are trying to be helpful; 14% center on whether calling out others on social media is a productive behavior or not; 10% focus on whether free speech or creating a comfortable environment online is more important; 8% address the perceived agendas of those who call out others; and 4% focus on whether speaking up is the best action to take if people find content offensive.

The most common area of opposing arguments about calling out other people on social media arises from people’s differing perspectives on whether people who call out others are rushing to judge or instead trying to be helpful.

One-in-five Americans who see this type of behavior as a form of accountability point to reasons that relate to how helpful calling out others can be. For example, some explained in an open-ended question that they associate this behavior with moving toward a better society or educating others on their mistakes so they can do better in the future. Conversely, roughly a third (35%) of those who see calling out other people on social media as a form of unjust punishment cite reasons that relate to people who call out others being rash or judgmental. Some of these Americans see this kind of behavior as overreacting or unnecessarily lashing out at others without considering the context or intentions of the original poster. Others emphasize that what is considered offensive can be subjective.

The second most common source of disagreement centers on the question of whether calling out others can solve anything: 13% of those who see calling out others as a form of punishment touch on this issue in explaining their opinion, as do 16% who see it as a form of accountability. Some who see calling people out as unjust punishment say it solves nothing and can actually make things worse. Others in this group question whether social media is a viable place for any productive conversations or see these platforms and their culture as inherently problematic and sometimes toxic. Conversely, there are those who see calling out others as a way to hold people accountable for what they post or to ensure that people consider the consequences of their social media posts.

Pew Research Center has studied the tension between free speech and feeling safe online for years, including the increasingly partisan nature of these disputes. This debate also appears in the context of calling out content on social media. Some 12% of those who see calling people out as punishment explain – in their own words – that they are in favor of free speech on social media. By comparison, 10% of those who see it in terms of accountability believe that things said in these social spaces matter, or that people should be more considerate by thinking before posting content that may be offensive or make people uncomfortable.

Another small share of people mention the perceived agenda of those who call out other people on social media in their rationales for why calling out others is accountability or punishment. Some people who see calling out others as a form of accountability say it’s a way to expose social ills such as misinformation, racism, ignorance or hate, or a way to make people face what they say online head-on by explaining themselves. In all, 8% of Americans who see calling out others as a way to hold people accountable for their actions voice these types of arguments.

Those who see calling others out as a form of punishment, by contrast, say it reflects people canceling anyone they disagree with or forcing their views on others. Some respondents feel people are trying to marginalize White voices and history. Others in this group believe that people who call out others are being disingenuous and doing so in an attempt to make themselves look good. In total, these types of arguments were raised by 9% of people who see calling out others as punishment.

Total Posts: 12577

Total Posts: 12577 Total Topics: 4980

Total Topics: 4980 Online Today: 176

Online Today: 176 Online Ever: 816

Online Ever: 816 Total Posts: 12577

Total Posts: 12577 Total Topics: 4980

Total Topics: 4980 Online Today: 176

Online Today: 176 Online Ever: 816

Online Ever: 816